Preface by Kyrylo Galushko, coordinator of the “Likbez. Historical Front”

The educational public project “Likbez. Historical Front” would like to assert the professional opinion of the Ukrainian historians on the official Russian interpretations of the Second World War events. As an informal community Likbez does not at all claim to “monopolize” assessments on behalf of all Ukrainian colleagues. A number of theses recently voiced by the President of the Russian Federation V. Putin received the necessary critical comments from the official bodies of the Central and Eastern European states, as well as from our fellow historians, in particular in Germany. In this situation, the Institute of the History of Ukraine of the National Academy of Sciences as an academic structure cannot provide “generalizing assessments”. The Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance is a state body, and its position (if it was voiced on this issue) would be political. We believe that the Ukrainian historical department has the right to give generalized professional assessments at the level of public initiatives, so that this information can be used by the media and the public as a qualified opinion of experts.

On June 18, 2020, on the eve of the 79th anniversary of the German-Soviet war outbreak, Vladimir Putin published his keynote article “The Real Lessons of the 75th Anniversary of World War II”.

The National Interest, The American conservative magazine, published by the American-Russian political scientist Dmitry Simes, became the platform for the policy document publication. The very next day, a Russian-language version of Putin’s article appeared on the Kremlin’s website.

As a matter of fact, there is nothing new either in the article itself or in the practice of such messages. Putin’s article uses the standard arguments of Soviet historiography, which places the primary responsibility for World War II incitement on Western countries. In particular, the emphasis is placed on the “Munich Betrayal” – the Munich Agreement of 1938, during which the Czechoslovak statehood was liquidated.

The very rhetoric of the article alludes to another document significant for Soviet historical policy – the report of the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Leonid Brezhnev “The Great Victory of the Soviet People”, timed to coincide with the 20th victory anniversary. The report was read on May 8, 1965 at a solemn meeting in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses. It marked the beginning of the Soviet cult of the “Great Victory”, which modern Russia actively supports to this day. These two documents have a lot in common.

First of all, Putin’s article is also timed to coincide with another anniversary – the 75th victory anniversary. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the Russian authorities were forced to postpone the pompous celebration from May 9 to June 24. However, the latter date is also not accidental. It was on June 24, 1945 that the first victory parade took place on Red Square.

Secondly, just as in the Brezhnev report, in Putin’s article history is also a tool for advancing the Russian agenda on the international arena. It is no coincidence that Putin draws parallels between the heroism of the Red Army, which fought against Nazism, and modern Russian soldiers who are “fighting” international terrorism in the North Caucasus and Syria.

Thirdly, in his article, Putin directly uses terms and theses of the Soviet 1965 model:

“At the summit of CIS leaders held at the end of last year, we all agreed on one thing: it is essential to pass on to future generations the memory of the fact that the Nazis were defeated first and foremost by the Soviet people and that representatives of all republics of the Soviet Union fought side by side together in that heroic battle, both on the frontlines and in the rear.”

The latter statement is clearly at odds with Putin’s speeches during 2010, when the Russian leader said that the war was won “mainly by the expense of the human and industrial resources of the Russian Federation.”

The change in rhetoric speaks for itself. A detailed analysis of Russia’s vision of the international relations future is presented in the article by the director of the National Institute for Strategic Studies Alexander Litvinenko “An Invitation to Yalta“. As the author rightly notes, Putin uses historical arguments to bring UN Security Council members to the negotiating table and divide the world again, and also justifies the annexation of Crimea.

Putin’s article was originally designed for both internal and external audiences and has caused controversy among experts. Russian historian Alexei Miller noted the organizational failure of this initiative, which, in his opinion, nullified the efforts of the Russian presidential administration.

It would seem the resonance of Putin’s program article has exhausted itself at that point. However, on June 23 Putin’s article was again discussed with renewed vigor. This time the news making topic was the dispatch of the German-language version of the article to the leading German experts on World War II by the Russian Embassy in Germany. The German historical community was particularly outraged by the Russian embassy press service recommendation to use Vladimir Putin’s article for preparation of the future historical materials. This was seen as an infringement on the freedom of science, even among those historians who partially supported certain theses of the article.

The press service of the Russian embassy in Germany hastened to clarify that the newsletter is of an exclusively informative nature and is intended to help users make an objective judgment about the material. The question whether the actions of the Russian embassy were a deliberate provocation or just an annoying misunderstanding remains unanswered. However, the desired effect was achieved – Putin’s program article began to be widely discussed in the European media, including the Ukrainian ones.

The majority of the theses presented in Putin’s article have already been repeatedly refuted by historians. Project “Likbez. Historical Front”, has been systematically fighting against historical fakes and myths since 2014. Consequently we could not ignore this incident. Firstly, this article is a program one; therefore, it defines Kremlin’s historical policy in the post-Soviet countries. The experience of the past six years has shown that the information component of hybrid warfare should not be underestimated. Secondly, in view of the 75th anniversary of the World War II conclusion, it will be appropriate to talk about its Ukrainian context and the traumas that are yet to be overcome.

In general, Putin’s article is an illustrious example of historical relativism. He is creating an optical illusion, so to speak, overemphasizing certain figures and hiding or distorting the others.

The article is full of quotes from historical documents. It calls to open the archives, following Russia’s example (sic!), and to create joint research projects. Putin was outraged by the Resolution of the European Parliament of September 19, 2019 “On the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe”, which equally blames Germany and the USSR for unleashing the Second World War. The Russian president considers this position unfair and insists that the road to war was paved not by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, but by the “Munich Betrayal”.

The Russian president claims that this declaration carries real threats and accuses the European Parliament of deliberate policy in order to destroy “the post-war world order whose creation was a matter of honor and responsibility fore states a number of representatives of which voted … of this deceitful resolution. Thus, they challenged the conclusions of the Nuremberg Tribunal and the efforts of the international community to create after the victorious 1945 universal international institutions. Let me remind you in this regard that the process of European integration itself leading to the establishment of relevant structures, including the European Parliament, became possible only due to the lessons learnt form the past and its accurate legal and political assessment.”

Putin is right in one regard. The European Union was really created owing to the lessons learned from the Second World War. But it was the Russian Federation that, by the annexation of Crimea, violated the main principle of the post-war world order, which maintained the borders inviolability of the states created after the Second World War. It is Russia that systematically and consistently uses the old Soviet methods to “incorporate” new territories, violating the basic principles of international law.

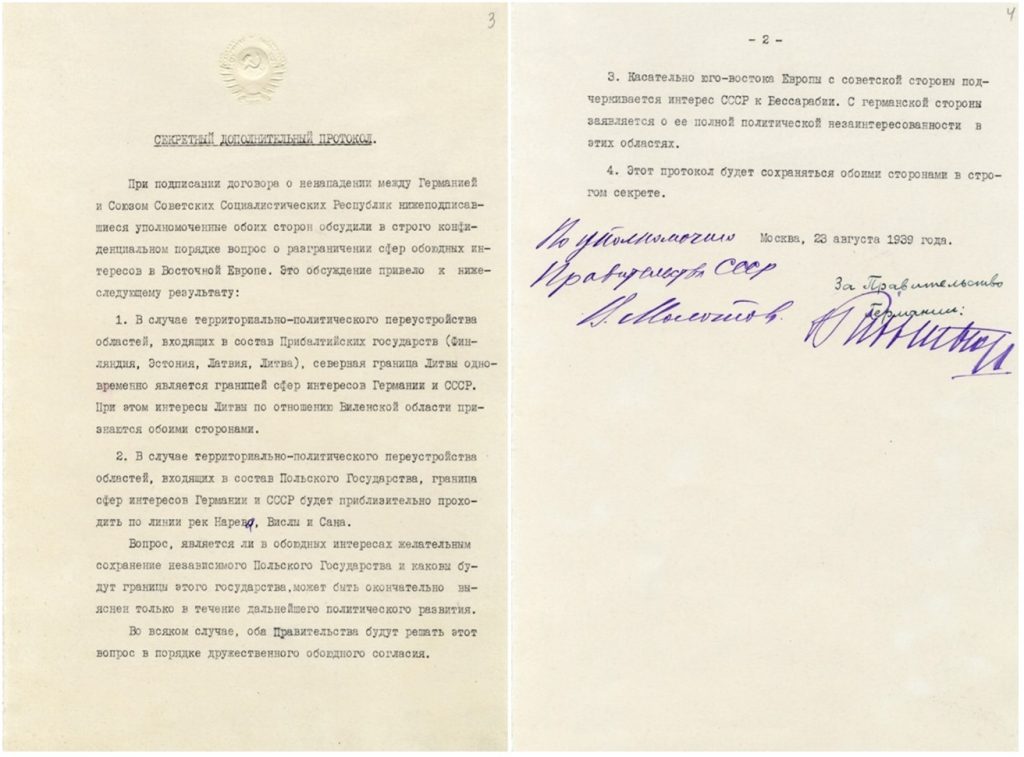

So what did V. Putin emphasize and what historical events did he keep silent about? As a matter of fact, historians will hardly see anything new in Putin’s policy article, only the standard set of arguments developed by Soviet historiography. The only innovation is the acknowledgement of the existence of a secret protocol to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Here however many aspects were also deliberately concealed. The article can be divided into three topics that the Russian president reflects upon: 1) responsibility for inciting World War II; 2) the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the secret protocol; 3) Nazi abettors and collaborators. These are three complex topics arranged in the above sequence. In conclusion, the Russian president invites the UN Security Council members to return to the spirit of the Yalta agreements and divide the world into spheres of influence.

Topic #1. Who started World War II?

One can hear a bitter resentment in Putin’s argumentation about the injustice of blaming Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union for inciting World War II equally. The Russian president notes:

“Stalin and his entourage, indeed, deserve many legitimate accusations. We remember the crimes committed by the regime against its own people and the horror of mass repressions. In other words, there are many things the Soviet leaders can be reproached for, but poor understanding of the nature of external threats is not one of them. … Nowadays, we hear lots of speculations and accusations against modern Russia in connection with the Non-Aggression Pact signed back then. Yes, Russia is the legal successor state to the USSR, and the Soviet period – with all its triumphs and tragedies – is an inalienable part of our thousand-year-long history. However, let us recall that the Soviet Union gave a legal and moral assessment of the so-called Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The Supreme Soviet in its resolution of 24 December 1989 officially denounced the secret protocols as “an act of personal power” which in no way reflected “the will of the Soviet people who bear no responsibility for this collusion”.

This is followed by accusations against Western democracies as the main architects of the Versailles system and donors to the German economy, which together laid the foundations for German revanchism. The policy of the aggressor appeasement, the apotheosis of which is the “Munich Agreement”, is harshly criticized. In this regard, Poland is especially blamed and accused not only of aiding the aggressor, but also of encouraging its plans.

Putin once again refers to the words of the Polish Ambassador to Germany J. Lipski during his conversation with Hitler on September 20, 1938: “… For solving the Jewish problem, we [the Poles] will build in his honor … a splendid monument in Warsaw.” This statement by the Russian president in December 2019 led to a diplomatic scandal with Poland.

Polish historian Marek Kornat explains that the quote was taken out of context. The topic of the cited conversation was the extension of the Polish-German non-aggression treaty of 1934. Hitler told Lipski about his intention to settle the Jewish issue by organizing the emigration of Jews to Africa, which was followed by the remark cited by Putin. The exact context of Lipski’s phrase is not fully known. Such a statement does not honor the Polish ambassador, but of course it is impossible to speak of it as a real readiness of Poland to erect a monument to Hitler. Moreover, during the conversation with Hitler, it became obvious to Lipski that Poland and Germany would not be able to reach any agreement on the extension of the treaty. Germany proposed conditions unacceptable for Poland.

This reasoning along with accusations of Poland’s involvement in the partition of Czechoslovakia, allows Putin to blame the Polish leadership of the time for the 1939 national tragedy. The Polish ambassador’s phrase taken out of context is intended for instrumentalization of the Holocaust theme. This will be discussed below in greater details.

Putin labels the partition of Czechoslovakia as “brutal and cynical.” Whereas the partition of Poland, based on the above, is not so much an act of aggression but the result of the wrong policy of the Polish leadership. This is a vivid example of relativism, where the theme of the “Munich Agreement” serves the sole purpose – to justify the subsequent partition of Poland. Putin wishes if not to remove the blame for inciting war from the Soviet Union, then at least to share responsibility with the Western democracies. Russian president places responsibility for the rise of Nazism primarily on the United Kingdom and the United States, and calls for legal and political responsibility for cooperation with Hitler. At the same time, Putin is silent about the economic, political and military cooperation between the USSR and Germany. He also forgets to mention that the USSR, along with Germany, also sought to revise the results of the First World War.

On August 19, 1939, the USSR and Germany signed a broad economic agreement. Until June 22, 1941, the Soviet Union supplied Nazi Germany with 865 thousand tons of oil, 140 thousand tons of manganese ore, 14 thousand tons of copper, 3 thousand tons of nickel, more than 1 million tons of timber, 2 736 kg of platinum, about 1.5 million tons of grain. Thus, the USSR supplied the German military machine in the first stage of the Second World War. During this period, Germany fought on the Western Front against Great Britain. Invasion of Denmark, Norway, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands and France was also achieved during this time.

On the same date, August 19, 1939, while speaking at the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party meeting with the participation of the Comintern representatives, Stalin declared the need to push Europe towards war. As only a big war could ensure the communists coming to power in European countries. Thus the Soviet Union was by no means a “dove of peace.” Stalin’s calculation was simple: to wait until the Western opponents exhausted each other, and to march victoriously across Europe, carrying the “proletarian revolution” on the bayonets of the Red Army.

The partition of Czechoslovakia was indeed an outrageous act and contributed to the process of unleashing the war. Actually, no one denies this. Attempts by Great Britain and France to avoid the war in this way were a fiasco. The Munich agreements were condemned by the general public in the United States, Great Britain and France, and Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier suffered political responsibility for their diplomatic miscalculations and were removed from their posts. The latter ended up in a Nazi concentration camp, and then in prison. The same cannot be said about Stalin, who, even after the failure of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and catastrophic defeats during the first stage of the German-Soviet war, remained in power. Moreover, for many years after the war, he was the sole dictator of the one sixth of the Earth land surface, a generalissimo and a living personification of victory in the “Great Patriotic War.”

The main fundamental difference between the Munich agreements, for all their flagrant violation of international principles, and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, is its open nature and the absence of a secret protocol.

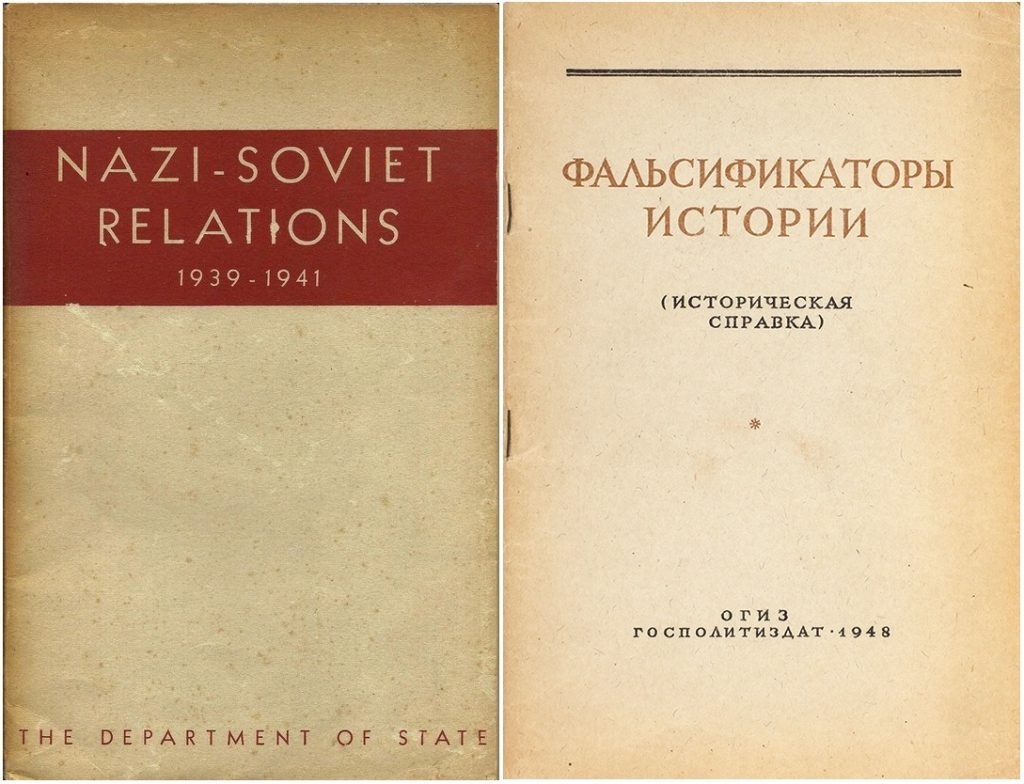

The Soviet Union indeed gave a legal and moral assessment to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1989. Fifty years after its signing in fact. The Soviet leadership denied the existence of a secret protocol for a long time. In 1948 a brochure titled “The Falsifiers of History“ was published in the USSR in response to the US publication of captured German documents collection concerning the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The stylistics analysis of the brochure suggests that Stalin himself was its author. The text outlined the Soviet interpretation of the late 1930s events in Europe, promoting the thesis of the consistent peace-loving policy of the Soviet Union and the opportunist activities of Western democracies. The arguments of the Russian president are largely derived from this brochure.

As seen from Putin’s policy article the Russian leadership continues to justify the expediency of this pact. Moreover, a number of representatives of the Russian political elite and members of the Russian Military-Historical Society have repeatedly spoken about the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as an outstanding achievement of Soviet diplomacy. Moreover a bill on the abolition of the USSR Supreme Soviet resolution on the legal assessment of the Soviet-German non-aggression pact of 1939 is still pending in the State Duma.

Topic #2. Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact: the secret protocol

In his article Putin defends the peaceful disposition of the USSR to the last. The Russian President states:

“Soviet Union sought to avoid engaging in the growing conflict for as long as possible and was unwilling to fight side by side with Germany was the reason why the real contact between the Soviet and the German troops occurred much farther east than the borders agreed in the secret protocol. It was not on the Vistula River but closer to the so-called Curzon Line, which back in 1919 was recommended by the Triple Entente as the eastern border of Poland.”

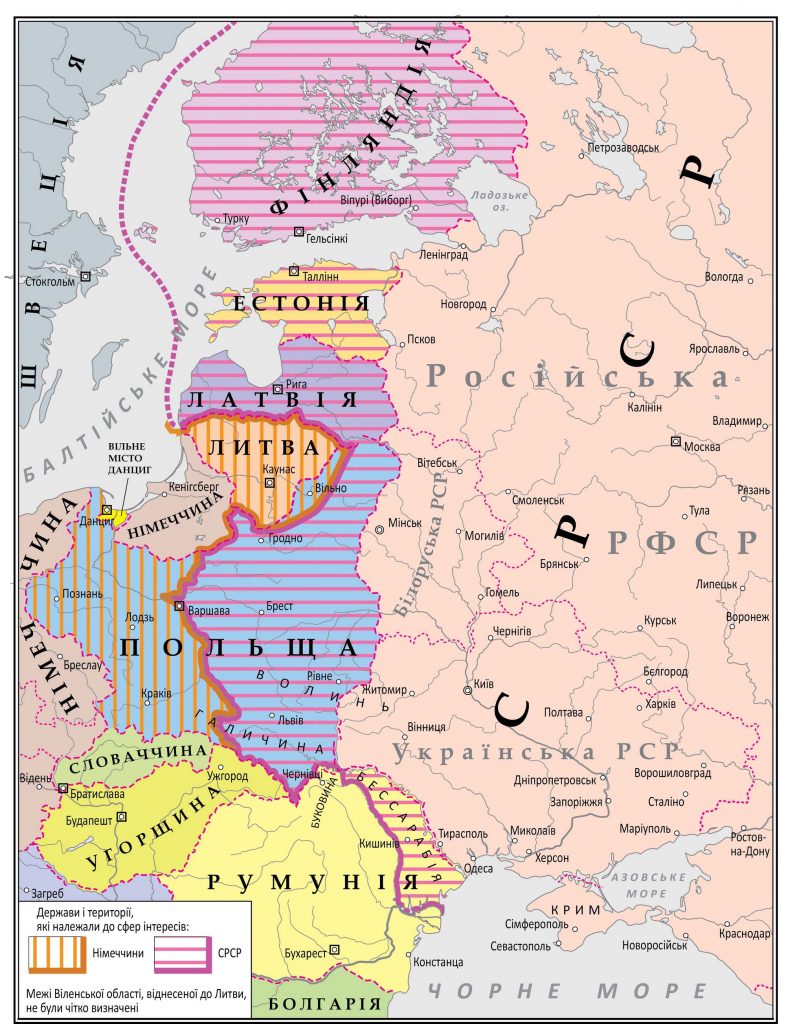

Had not Stalin wanted to play on the side of Germany, there would be no Secret Additional Protocol on the partition of the six European states territories into the spheres of interest. The territories that were previously part of the Russian Empire (part of eastern Poland, Finland, Latvia, Estonia and Bessarabia) fell into the Soviet sphere. In fact, Stalin restored the “one and indivisible Russia” under the guise of rhetoric about helping the fraternal nations.

What the Soviet Union was really striving for in September 1939 was not to receive a declaration of war from Great Britain and France. It was not the aggression against the weaker and more preoccupied with war with Germany Poland that Stalin was trying to avoid, but responsibility for this aggression.

That is why Stalin delayed the invasion, while looking for a plausible pretext and watching the reaction of Poland’s allies to the Nazi aggression. The Russian president himself sheds some light on this with his “Freudian slip”:

“Only when it became absolutely clear that Great Britain and France were not going to help their ally and the Wehrmacht could swiftly occupy entire Poland and thus appear on the approaches to Minsk that the Soviet Union decided to send in, on the morning of 17 September, Red Army units into the so-called Eastern Borderlines, which nowadays form part of the territories of Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania. “

Both Stalin and Hitler realized that an attack on Poland threatened the beginning of a world war. However, the passive reaction of Great Britain and France to the Anschluss of Austria and the takeover of Czechoslovakia gave both dictators reason to believe that Western democracies would not rise to defend Poland.

Nevertheless, on September 3, 1939, after Hitler’s invasion of Poland, Great Britain and France declared war upon Germany. Immediate support of the Wehrmacht by the Red Army in Poland could also bring the USSR into a state of war with Western democracies. Stalin had reason to fear a direct military confrontation with the former Entente. However, Poland’s allies were not up to par this time. The beginning of their confrontation with Germany went down in history under the name of the “strange war”, since no serious action followed its declaration.

These developments strengthened Stalin’s confidence that he could get away with aggression. However just to make sure it was worth waiting for Poland to capitulate or otherwise show an inability to resist. (Later on, Soviet propaganda would claim that the advance of the Red Army into Poland began after Polish government fled the country, however everything happened in the precisely reverse order.)

Time passed, and following its military interests the Wehrmacht began to occupy the part of Poland that was previously agreed to be the USSR sphere of interests. As a result, the Red Army did not reach the Vistula River. It was already inappropriate to insist on the agreed territorial demarcation, since the USSR did not come to Hitler’s aid in time. Therefore, Stalin abandoned Lublin, inhabited mainly by Poles, as well as parts of the Warsaw, Bialystok and Lviv provinces.

It was not accidental that Putin mentioned the so-called Curzon line. The Stalinist diplomats began to appeal to the Curzon line not to Ribbentrop in 1939 but rather to the Western allies after 1941, when the post-war border of the USSR was being decided. Stalin manipulated historical facts to legitimize his acquisitions in Poland: he insisted that the British Foreign Minister himself once offered the Bolsheviks these lands.

The decision to give up part of the sphere of interests fit well into the pre-fabricated legend about helping the Western Ukrainians and Belarusians abandoned to their fate. Since it was a question of “reuniting” their lands with the corresponding Soviet republics, the Polish ethnic territories on the right bank of the Vistula no longer had a place in the USSR.

The documents demonstrate that the decision to provide information cover for the capture of Poland was made on September 6. On September 7 Stalin already met with the General Secretary of the Comintern Executive Committee G.Dimitrov and explained to him that Poland is a fascist state that oppresses Ukrainians and Belarusians. Needless to say before this meeting, the Comintern actively supported Poland as a victim of German aggression.

Stalin’s political somersaults caught Hitler by surprise. However, he was already bogged down in the war and did not want to quarrel with the Soviet Union. Ribbentrop’s weak protests against the rationale of the Red Army Polish campaign as “liberation” were unsuccessful.

On September 14 Pravda newspaper published an article “On the internal reasons for the defeat of Poland”. The article stated the internal contradictions of the multinational Polish state and its repressive policy towards national minorities as the main reason of the Polish army defeat. Thus, the information preparation was completed and on September 17 the Red Army began its “liberation march”.

This gives us a reason to conclude that the territorial expansion of the USSR into the west caused by Stalin’s activity positioned as “bringing together of the Ukrainian lands” does not fit into reality.

A new demarcation line was established on the emerged Soviet-German border on September 22 and the success of the campaign was honored by a joint parade of German and Soviet troops in Brest.

The thesis that the Soviet Union was forced to divide Poland also does not withstand the test of historical facts:

“Obviously, there was no alternative. Otherwise, the USSR would face seriously increased risks because – I will say this again – the old Soviet-Polish border ran only within a few tens of kilometers of Minsk. The country would have to enter the inevitable war with the Nazis from very disadvantageous strategic positions, while millions of people of different nationalities, including the Jews living near Brest and Grodno, Przemyśl, Lvov and Wilno, would be left to die at the hands of the Nazis and their local accomplices – anti-Semites and radical nationalists.”

The major defeats in 1941 demonstrated that, first, the USSR was unable to take advantage of the new “advantageous” strategic positions; secondly, the annexation of new territories to the Soviet Union turned into massive repressions for their inhabitants. From the territory of Western Ukraine alone, from the fall of 1939 to the summer of 1941, 900 thousand people were deported, including 600 thousand Poles, 200 thousand Ukrainians, and 80 thousand Jews who fled from Central Poland.

Stalin’s refusal to claim part of the Polish territories made it necessary to sign the Treaty of Friendship and the Border between the USSR and Germany on September 28. In exchange for the Polish territories that were ceded to Germany, the Soviet dictator wished to include Lithuania into his sphere of interests. This brings us directly to the topic of “incorporation” of the Baltic States.

This part of the plot deserves more attention. As the Russian president writes:

“In autumn 1939, the Soviet Union, pursuing its strategic military and defensive goals, started the process of the incorporation of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. Their accession to the USSR was implemented on a contractual basis, with the consent of the elected authorities. This was in line with international and state law of that time. Besides, in October 1939, the city of Vilna and the surrounding area, which had previously been part of Poland, were returned to Lithuania. The Baltic republics within the USSR preserved their government bodies, language, and had representation in the higher state structures of the Soviet Union.”

What have actually happened?

The USSR deployed troops along the borders of the Baltic republics in September 1939. Their number exceeded the armies of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia combined. In the absence of an influential external ally, the Baltic countries were doomed. The Soviet-Estonian pact of mutual assistance was signed on September 28 under pressure from the Soviet Union for a period of ten years, which de facto limited the republic’s sovereignty. The 25,000-strong contingent of the Red Army entered the territory of Estonia. Strategic Baltic Sea ports were transferred to the USSR. Similar agreements were signed with Latvia on October 5 and with Lithuania on October 10.

On June 14, 1940, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum to Lithuania, and on June 16 to Latvia and Estonia. The Baltic republics were accused of violating the terms of the treaties. The Soviet side put forward ultimatum conditions: to form new governments that will “ensure the fulfillment of treaties” and increase the Soviet military contingent in the territories of the Baltic republics. Acceptance of these conditions meant complete annexation, but the forces were unequal. On June 15, additional troops of the Red Army were brought into Lithuania, and on June 17 – into Latvia and Estonia.

During the elections held on July 14, the pro-communist blocs, the Unions of the Working People, won in all states. These were the only electoral lists accepted for the elections. Thus, loyal pro-Moscow governments were formed, that swiftly proclaimed the creation of the Lithuanian SSR, the Latvian SSR and the Estonian SSR on July 21-22. Moreover the declarations on joining the USSR were signed.

On August 3-6, 1940 the Supreme Soviet of the USSR formally admitted the Baltic republics to the Soviet Union. Thus the legalization of the annexation was completed and the process of Sovietization began, accompanied by repressions and mass deportations of the local population to Siberia.

A similar scenario was used by Putin during the annexation of Crimea, as well as organization of pseudo-referendums in Donbas.

The Winter War plays a role of a silent figure in Putin’s article. The topic of the Soviet-Finnish war has been unpopular in Russian political discourse since the days of the USSR. The price of Stalin’s political adventure was too high for the Soviet Union, and the achievements were very ambiguous. The war itself was obviously aggressive and did not fit into the coherent concept of the Russian president. The League of Nations expelled the USSR because of the war against Finland, and Putin criticizes the League profoundly in his article.

The second inconvenient fact undermining the image of the USSR as a “peace-loving state” was the Katyn massacre of 1940.

In the article Putin deliberately separates the heroism of the Polish soldiers and the adventurous policies of the Polish state during the inter-war period. This favorite Bolshevik technique is intended to show the community and unity of the Soviet (and now, as we see, the Russian) government with ordinary working people in the struggle against exploiters (usurpers, junta, etc.). However, such an attempt cannot withstand the facts, since a natural question arises: why was it necessary to shoot the Polish officers, the very everyday heroes with whom the Bolsheviks loved to demonstrate their solidarity rhetorically?

This part of Putin’s policy article is replete with relativism, sophistry, silence on the crimes of the Soviet regime and juggling facts wherever possible.

Topic #3. Nuremberg Tribunal, Nazi abettors and collaborators

If the previous topics are presented in the form of lengthy arguments replete with links to archival documents, the topic of Nazi accomplices was awarded only one succinct paragraph. The latter is not surprising. After all, if in the first part of the article, Putin acts as a lawyer who is inclined to talk about difficult contexts and realities, in the second case he is an unforgiving accuser:

“Directly and unambiguously, the Nuremberg Tribunal also condemned the accomplices of the Nazis, collaborators of various kinds. This shameful phenomenon manifested itself in all European countries. Such figures as Pétain, Quisling, Vlasov, Bandera, their henchmen and followers – though they were disguised as fighters for national independence or freedom from communism – are traitors and slaughterers. In inhumanity, they often exceeded their masters. In their desire to serve, as part of special punitive groups they willingly executed the most inhuman orders. They were responsible for such bloody events as the shootings of Babi Yar, the Volhynia massacre, burnt Khatyn, acts of destruction of Jews in Lithuania and Latvia.” (underlined by the author – Y.P.)

Ukrainian historians will not discover anything new in this statement either. Two theses have long and consistently been promoted in Russian public discourse: 1) Ukrainians were the main collaborators and accomplices of the Nazis; 2) Ukrainian nationalists were ardent anti-Semites who excelled the Nazis in their atrocities.

The Nuremberg Tribunal really did condemned accomplices and collaborators of all stripes and nationalities, but despite the USSR best efforts neither the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), nor S.Bandera are on this list. Moreover, Bandera himself was imprisoned by the Nazis from July 1941 to the autumn of 1944; he spent most of this time in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. All this time Bandera had no connection with the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists), remaining only a formal leader and a symbol of the persistent struggle for the independence of Ukraine. Bandera’s political views were indeed right and primarily anti-Polish.

In between the wars Stepan Bandera was the organizer of two resonance political assassinations in Poland. These were attempts on the lives of Bronisław Pieracki, the Polish minister of the internal affairs, and Aleksei Mailov, the Soviet Consulate secretary. The first assassination was a payback for the Pacification and the second for Holodomor. During the courts hearings that took place in Warsaw and Lviv Bandera and his supporters used the court for proclamation of their political views. Bandera was sentenced to death but later the sentence was changed to life in prison. In fact Bandera was imprisoned in Poland from 1934 to 1939.

The ideological inheritance of OUN is not straightforward because the movement was not united. In 1943 the Bandera wing of OUN changed its position towards democratization. However Bandera himself did not support the changes, which only made the split in organization deeper. After the war OUN movement developed in immigration and had its own specifics.

OUN/UPA – are parts of the Ukrainian history, Ukrainian independence movement, and is being researched in depth in the independent Ukraine and abroad. Putin proposes to get back to the cliché of Soviet propaganda and in this way undermines his own suggestion to research the World War II from different sides. It seems that Russian government is interested in becoming the head of the research process and to stir it in the desired direction, and not interested in searching for the historical truth.

Putin is purposefully confuses Ukrainian freedom movement OUN/UPA with the abettors – Ukrainian auxiliary police that was formed from the local population as well as from the Soviet prisoners of war. Moreover Ukrainian police received its name by territorial and not by national principle. It consisted not only from Ukrainian but from other nationals as well. All of them were punished during the court hearings of 1940-1950 and sentenced for 8 to 15 years in the camps.

Let us note that the population in the occupied territories was abandoned by the Soviet government to its own fate. Moreover during the retreat the Red Army used the “burnt land” tactic that made the corridor of survival even narrower. Soviet prisoners of war, who were massively captured as the result of Stalin’s incompetent command, went into the service of the Nazis with the sole purpose – to break free from the German camps and to survive. The moral dilemma was indeed terrible.

The tragedy of Babi Yar is increasingly instrumentalized by the Russian leadership, so it is worthwhile to turn to the facts. The executioners of Babi Yar have long been well known to historians:

1) Units from the Aisanzgroup C

- Sonderkommando 4a (commander – SS Standartenfuehrer Paul Blobel);

- Aisantskommando 5 (commander – SS Sturmbannfuehrer August Mayer);

- 3rd company of the 9th reserve police battalion (commander – police captain Walter Krumme);

- 3rd company of the SS special forces battalion (commander – SS Obersturmführer Bernard Grafgorst);

2) Units subordinate to the commander-in-chief of the SS and police “Russia-South” SS Obergruppenfuehrer Friedrich Ekkeln

- Police Regiment “South” (commander – Police Colonel Rene Rosenberg);

- “Headquarters company” (volunteer firing squad);

- 45th reserve battalion (commander – Police Major and SS Sturmbannfuehrer Martin Besser)

- 303rd battalion (commander – Police Major and SS Sturmbannfuehrer Heinrich Hannibal)

3) The field gendarmerie and parts of the Wehrmacht were also involved (454th security division, 75th and 299th infantry divisions)

Obviously, the participation of the local (“Ukrainian”) police and the characteristics of its contingent have the greatest resonance. The local police was indeed present at Babi Yar. It was recruited as support personnel during the executions and did not take part in the executions. Who were those three hundred Ukrainian policemen who were in Kyiv during the mass executions at Babi Yar in 1941? The research shows, that for the most part these were not committed Ukrainian nationalists, but ordinary Soviet prisoners of war.

The topic of the Bukovinian kuren OUN (m), which allegedly took part in the executions at Babi Yar in September 1941, was investigated in detail. It was established that the kuren arrived in Kiev in November 1941, and, therefore, could not participate in the executions.

We also note that Ukrainian nationalists who worked in the occupation administration of Kyiv belonged to A.Melnik’s OUN faction. In February 1942, almost all of them were shot by the Nazis at Babi Yar. Among them was the Ukrainian poet Olena Teliha.

Since September 1941, after the assassination of the leading figures of the OUN (m) O.Senyk and M.Stsiborsky, the Banderaites were outlawed by the occupation authorities.

Clearly some of the Ukrainians, some members of the OUN among them, were really involved in the Holocaust. Ukrainian historians write and talk about this involvement and collaboration. Putin, on the other hand, uses the old Soviet formula of the mythical “Banderaites” to accuse not only the Ukrainian insurgent movement, but also to discredit Ukrainians in general. This is a classic example of the instrumentalization of history.

The Khatyn tragedy is another example of how the Soviet Union and now the Russian Federation are using history to advance their political agenda. Firstly, Khatyn diverted attention from the Katyn crime due to the similarity of names. Secondly, the Soviet side wanted to use the process against the 118th Schutzmanschaft battalion, initiated in the BSSR in 1985, to discredit the Ukrainian organizations of the USA and Canada. The case was presented in such a way that accused Ukrainian nationalists as the Khatyn executioners. In truth, the 118th Schutzmannschaft battalion consisted of the Soviet prisoners of war – Ukrainians, Russians, Belarusians.

This list would be incomplete without the mention of the Volhynia tragedy, which is traditional for Russian historical discourse. The events of the summer of 1943 in Volhynia are part of the larger Ukrainian-Polish conflict of 1943–44, which, according to various estimates, claimed the lives of 70,000 to 100,000 Poles and 15,000 to 20,000 Ukrainians.

On July 22, 2016, the Polish Sejm adopted a resolution, according to which July 11 was declared the “National Day of Remembrance for the Victims of the Genocide Perpetrated by Ukrainian Nationalists against the Citizens of the Second Polish Republic in 1943-45.”

Note that the same decree condemns the actions of Polish armed formations against peaceful Ukrainians during the Second World War, and also expresses support for Ukraine in the fight against “external aggression”.

The decision of the Polish Sejm was met with mixed reception by Ukrainian experts, many of whom interpret the Volhynia events as an episode of the second Ukrainian-Polish war of 1942-1947, where the UPA and the Home Army (Armia Krajowa) were the opposing sides. The conflict was fueled by the Germans and Soviet partisans.

The Ukrainian-Polish reconciliation dialogue has been going on for two decades. During this time, historians of both countries have done an enormous amount of work, that resulted in the publication of a multi-volume documentary series Poland and Ukraine in the Thirty-Forties of the 20th Century. The historical debate on this issue is still ongoing.

Moreover, the dialogue of reconciliation is also taking place at the political level. In the summer of 2003, on the 60th anniversary of the Volhynia tragedy, President of Ukraine Leonid Kuchma and President of Poland Alexander Kwaśniewski took part in joint Polish-Ukrainian commemorative events.

On July 8, 2016, as part of the NATO Summit in Warsaw, President Petro Poroshenko honored the memory of the victims of the Volhynia tragedy. In July 2016, representatives of the Ukrainian and Polish public exchanged letters, the quintessence of which was the formula “forgive and ask for forgiveness”. However, the above mentioned decision of the Polish Sejm cooled the Ukrainian-Polish relations. At the moment we hope that this historical discussion has moved to a professional environment.

So Putin here clearly “did not discover America.” The Russian president’s speculations on this topic are nothing more than another attempt, to deepen the split between the strategic partners, Poland and Ukraine, by playing on national traumas.

The historical reasoning behind Putin’s program article pursues very specific pragmatic goals. As the German historian Karl Schlögel, a specialist in Eastern European history, points out:

[Putin] uses the interpretation of history as a tool for his current politics. This is an attempt to present Poland, Ukraine and the Baltic states as reactionary, nationalist and largely anti-Semitic states. This is an attempt to isolate the countries on whose territory a significant part of the horrors of war took place and that are concerned about their own security. If you make a connection with the parade on May 9 and June 24, this is the biggest offense for the Red Army, which fought against Hitler, – to use it in the confrontation with Ukraine, with Poland, who themselves became victims of the National Socialist policy and also fought against Hitler. Obviously, Putin is counting on at least some response from the Western public.

We see Putin’s clear interest in the countries of the Black Sea-Baltic region, which are of key geopolitical and strategic importance for the Russian Federation. Based on the foregoing, it can be predicted that the spearhead of Putin’s historical policy will be aimed at discrediting and returning these countries to the sphere of Russia’s orbit. The symbolic capital of the “Great Patriotic War” myth will be used for this once again. To this end, one can expect the strengthening of the instrumentalization of the Holocaust theme, as well as the inspiration of the Ukrainian-Polish confrontation in the field of historical politics, since these two countries are the key to the restoration of Russia’s superpower status.

Ukraine, Poland and the Baltic states will be equally exposed to information attacks on the historical field. Such attacks can be successfully countered only by consolidated efforts.

“One victory for all”: Ukrainian (con) text

So what was World War II for Ukraine? Why is it so important to convey the history of Ukraine and Ukrainians in the Second World War to Ukrainians and the world community?

Due to the fact that Ukrainians did not have a de facto state of their own during World War II, they ended up on opposite sides of the front and in different armies, and Ukraine itself became a bargaining chip in the hands of the greater powers.

In March 1939, the Ukrainians of Transcarpathia were one of the first in Europe to feel the breath of the approaching Second World War fire, when they faced the Hungarian occupation army on Krasne Pole.

In September 1939, 112 thousand Ukrainians entered into confrontation with the Wehrmacht troops as part of the Polish Army. Remaining faithful to the oath, about 8 thousand Ukrainians were killed and 16 thousand were wounded defending Poland.

Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians in the ranks of the Red Army took part in the invasion of the territory of the Second Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in heavy battles in Finland, in the occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina.

From the first days of the Nazi invasion of Soviet territory, Ukraine became the scene of bloody battles. The first big battles on the eastern front are the Volhynia tank battle, the defense of Kyiv, Odessa, Sevastopol. Two large encirclements took place in Ukraine – Uman and Kyiv (the largest in world history). 1.3 million Soviet soldiers were captured, including natives of Ukraine.

Until the end of the summer of 1941, 3.2 million people were mobilized into the ranks of the Red Army from the territory of Ukraine. Ukrainians made up 50% of the troops of the Southwestern Front. Even in 1942, when the territory of Ukraine was completely occupied, Ukrainians accounted for 8% of the active army, and in 1943 their part increased to 10-11%.

In 1943–1945 4.5 million people were drafted from Ukraine. From the second half of 1943, Ukrainians made up 60-80% of the soldiers in the units of the Ukrainian fronts.

Decisive battles on the Soviet-German front are associated with Ukraine. Sixty percent of the German ground forces were defeated there. In 1943–1944 12 offensive and 2 defensive operations were carried out on the territory of Ukraine.

The Ukrainians also fought against the Nazis in Soviet partisan units, in the ranks of the UPA, units of the French, Yugoslav and Slovak resistance movements. About 50 thousand Ukrainians took part in the war in the ranks of the Canadian, American, Australian and British armies.

Tens of thousands of Ukrainians believed Hitler’s propaganda and ended up in German military formations. Some of them sincerely hoped that Germany would create a full-fledged Ukrainian army on the basis of Ukrainian units and formations.

About 25 thousand Ukrainians in different periods served in the Waffen SS division “Galicia”, 8 thousand of them perished. 80 thousand served in the Ukrainian Liberation Army created by the Germans (Ukrainian – UVV), 5 thousand were part of the anti-tank brigade “Vilna Ukraina” (3 thousand – killed), 10 thousand – in the German air defense. About 80 thousand citizens of Ukrainian origin were in the ranks of the security police created by the Nazis in the occupied territories of Eastern Europe; 170 thousand ended up in the Order Service, and 180 thousand – in rural self-defense detachments to protect the harvest. How many of these people died during the hostilities have not yet been established.

As a result of the war, the population of Ukraine decreased by 10.4 million people. Direct losses amounted to 8 million people, of which 5 – 5.2 million civilians.

Military losses, according to the latest data, are estimated in the range from 2.8 to 3.3 million people. However, the figures for Soviet military losses still require clarification. During 1941–1942 2.4 million people were taken from the territory of Ukraine to forced labor in Germany.

714 cities, 28 thousand villages, 16.5 thousand industrial facilities, 2 million houses were completely or partially destroyed in Ukraine. 10 million people were left without a roof over their heads. The objects of humanitarian infrastructure were destroyed: 18 thousand hospitals, clinics and first-aid posts, about 33 thousand schools, 19 thousand libraries.

The Second World War forever changed the ethnic composition of Ukrainian society. In 1944, 200 thousand Crimean Tatars were deported from Crimea to Central Asia. Of the 3 million Jews, only 1.4 million survived the war. The number of Poles decreased from 2.5 million to 400 thousand as a result of the Polish-Ukrainian population exchanges in 1944-1946. At the same time, the number of Russians increased. In the first post-war decade, their number increased from 4 million to 7 million. In fact, Ukraine has turned from a multinational state with large ethnic minorities into a mono-ethnic state with a single large Russian national minority.

The formation of the modern borders and membership in the UN were important outcomes of the Second World War for Ukraine. The latter was the result of the recognition of Ukraine’s contribution to the victory over Nazism by the world community.

The legacy of World War II for Ukraine is ambiguous. The occupied territory of Ukraine was divided into several zones of occupation. As a consequence, the experience of war and the memory of it differ in different regions. This creates competition in the war memories. It is on this ambiguity that the Russian president continues to play, often using the old ideas of Soviet propaganda.

Illustrations without indicated sources are taken from open sources

Українська

Українська Русский

Русский