Mykhailo Hrushevsky. The traditional scheme of ‘Russian’ history and the problem of a rational organization of the history of the East Slavs

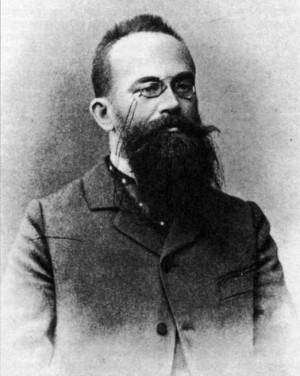

A short article under the title ‘The Traditional Scheme of “Russian” History and the Problem of a Rational Organization of the History of the East Slavs’ (in Ukrainian ‘Zvychaina skhema “rus’koi” istorii i sprava ratsional’noho ukladu istorii skhidnoho slov’yanstva’) Mykhailo Hrushevsky (1866–1934), a Ukrainian historian, wrote in September 1903. By then Hrushevsky was a well-known professor of Lviv University and a chairman of the Shevchenko Scientific Society, who managed to publish many articles and several volumes of documents on the history of Ukraine, three thick volumes of a multi-volume ‘History of Ukraine-Rus’, with the fourth volume on the way.

Hrushevsky was preparing ‘The Traditional Scheme…’ as a report for the International Congress of Slavists, which was to take place in St. Petersburg. The Congress, however, was cancelled, but Hrushevsky’s article was published in the first volume of the proceedings ‘Statji po slavyanovedeniyu’ [‘Essays on the Slavic Studies’] in St. Petersburg in 1904, edited by a renowned scholar Vladimir Lamansky. Due to the fact that the proceedings contained articles in foreign languages authored by the non-Russian Congress participants, Hrushevsky was able to publish his article in Ukrainian (we need to remember that since 1876 the publications of any kind in Ukrainian were strictly banned in the Russian Empire).

In this skimpy article Hrushevsky presented the sharpest, clearest, and most distinct summary of his arguments on contradictions within the historical narrative of the Russian Empire using the idea of a ‘rational’ construction of history of the Slavic peoples brought up by the Congress Organizing Committee. Thus Mykhailo Hrushevsky in fact laid the foundation of the Ukrainian historiography.

Here we present the English translation of the article according to the publication:

Hrushevsky, Michael. The Traditional Scheme of ‘Russian’ History and the Problem of a Rational Organization of the History of the East Slavs, ed. by Andrew Gregorovich. Second edition. Winnipeg, Canada: Published for Ukrainian Canadian University Students’ Union by the Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences, 1966, pp. 7–16. (SLAVISTICA: Proceedings of the Institute of Slavistics of the Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences. Editor-In-Chief J.B.Rudnyckyj, No. 55).

MYKHAILO HRUSHEVSKY

THE TRADITIONAL SCHEME OF ‘RUSSIAN’ HISTORY AND THE PROBLEM OF A RATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF THE HISTORY OF THE EAST SLAVS

The consideration by the Congress of Russian Philologists of a rational outline of Slavic history for the proposed Slavic Encyclopedia makes opportune a discussion of the problem of the presentation of East Slav history [1]. On more than one occasion I have touched upon the question of irrationality in the usual presentation of ‘Russian’ history [2]. At this time I should like to discuss the problem at greater length.

The generally accepted presentation of Russian history is well known. It begins with the pre-history of Eastern Europe, usually with the colonization by non-Slavs, then the settlement of the Slavs and the formation of the Kievan State. Its history is brought up to the second half of the 12th century, then it shifts to the Principality of Volodimir the Great, from here, in the 14th century, to the Principality of Moscow and then it follows the history of the Moscow State and then of the Empire.

As for the history of the Ukrainian-Ruś and Byelorussian lands that were left outside the boundaries of the Moscow State, several of the more significant episodes in their history are sometimes considered – the State of Danylo, the formation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Union with Poland, the Church Union, and the Khmelnytsky wars. Often they are completely left out, but in any case with their annexation by the Russian State these lands cease to be the subject of this history.

This is an old scheme which has its beginnings in the historiographic scheme of the Moscow scribes, and at its basis lies the genealogical idea – the genealogy of the Moscow dynasty. With the beginning of scientific historiography in Russia, this scheme served as a basis for the history of the ‘Russian State’. Later, when the chief emphasis was transferred to the history of the people, of the social structure and culture, and when ‘Russian history’ tended to become the history of the Great Russian people and its cultural life, the same scheme was retained in its most important phases, except that some episodes were omitted. As time went on, this occurred with ever greater frequency. The same arrangement, in simpler form, was adopted in the science of ‘the history of Russian Law’ the Law of the Kievan State, of Muscovy and the Empire.

In the first place, it is most irrational to link the old history of the Southern tribes, of the Kievan State and their socio-political organization, laws and culture with the Volodimir-Moscow Principality of the 13th and 14th centuries, as though the latter were the continuation of the first. This may have been permissible insofar as the Moscow scribes were concerned. The genealogical approach may have satisfied them. Modern science, however, looks for genetic connections and thus has no right to unite the ‘Kievan Period’ with the ‘Volodimir Period’ (as they are inappropriately called), as phases of the same political and cultural process.

We know that the Kievan State, its laws and culture, were the creation of one nationality, the Ukrainian-Ruś, while the Volodimir-Moscow State was the creation of another nationality, the Great Russian [3]. The Pogodin theory aimed to eliminate this difference by suggesting that the Dnieper regions of the 10th-12th centuries were colonized by Great Russians who emigrated from there in the 13th-14th centuries, but I doubt whether anybody today will defend the old historical scheme on the basis of this risky and almost neglected theory. The Kievan Period did not pass into the Voiodimir-Moscow Period, but into the Galician-Volhynian Period of the 13th century and later into the Lithuanian-Polish of the 14th-16th centuries.

The Volodimir-Moscow State was neither the successor nor the inheritor of the Kievan State. It grew out of its own roots and the relations of the Kievan State toward it may more accurately be compared to the relations that existed between Rome and the Gaul provinces than described as two successive periods in the political and cultural life of France. The Kievan government transplanted onto Great Russian soil the forms of a socio-political system, its laws and culture – all nurtured in the course of its own historical process; but this does not mean that the Kievan State should be included in the history of the Great Russian nationality. The ethnographic and historical proximity of the two nationalities, the Ukrainian and the Great Russian, should not give cause for confusing the two. Each lived its own life above and beyond their historical contacts and encounters.

By attaching the Kievan State to the beginnings of the governmental and cultural life of the Great Russian people, the history of the Great Russians remains in reality without a beginning. The history of the formation of the Great Russian nationality remains unexplained to this day simply because it has been customary to trace it from the middle of the 12th century [4]. Even with the history of the Kievan State attached, this native beginning does not appear quite clear to those who have studied ‘Russian history’. The process of the reception and modification of the Kiev socio-political forms, laws and culture on Great Russian soil is not being studied thoroughly. Instead, they are incorporated into the inventory of the Great Russian people, the ‘Russian State’, in the form in which they existed in Kiev, in Ukraine. The fiction of the ‘Kievan Period’ does not offer the opportunity to present suitably the history of the Great Russian nationality.

And because the ‘Kievan Period’ is attached to the governmental and cultural history of the Great Russian people, the history of the Ukrainian-Ruś nationality also remains without a beginning. The old viewpoint persists that the history of Ukraine, of the ‘Little Russian’ people, begins only with the 14th-15th centuries and that before this it was a part of the history of ‘all-Russia’. On the other hand, this ‘all Russian history’ concept, both consciously and unconsciously, is at every step substituted for the governmental and cultural history of the Great Russian people, with the result that the Ukrainian-Ruś nationality appears on the arena of History during the 14th-16th centuries as something quite new, as though it had not existed before or lacked a history of its own.

The history of the Ukrainian-Ruś nationality is left not only without a beginning but appears in piecemeal fashion as disjecta membra, disjointed organically, the periods separated one from the other by chasms. The only period that is distinct and remains clearly in mind is that of the Cossacks of the 17th century. I doubt, however, whether anyone studying ‘Russian history’ according to the usual scheme would be able to connect this period with the earlier and later phases of Ukraine’s history and to perceive this history in its organic entirety.

The Byelorussian nationality fares even worse under this traditional scheme. It is lost completely in the histories of the Kievan State, the Volodimir-Moscow State and in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Though nowhere in history does it appear clearly as a creative element, its role nonetheless is not insignificant. One might point out its importance in the formation of the Great Russian nationality or in the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, where the cultural role among the Slav peoples, in relation to the less developed Lithuanian tribes, belonged to the Byelorussians.

The one-sidedness and shortcomings of the traditional scheme were supposed to be improved by inclusion of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the ‘history of Russia’. It seems that it was Ustryalov who first, with considerable emphasis, brought forth this idea in historical writing. Ilovaisky, Bestuzhev-Ryumin and others tried to present in parallel fashion the history of ‘Western Rus’, that is of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and of ‘Eastern Rus’, that is of the Moscow State. In the history of law, the school of Professor Vladimirsky-Budanov propagandizes the need of including the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, though it has offered neither a general course in the ‘history of Russian law’ where the Grand Duchy of Lithuania would be included, nor a separate course in the law of Lithuania itself.

This is a correction but the correction itself needs various corrections. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a highly heterogeneous body, not at all homogeneous. Recently the significance of the Lithuanian factor has not only been depreciated, but has actually been ignored. Research into the inheritance of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the old Ruś law and the significance of the Slav element in the process of the creation and development of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania has led the contemporary researchers in the internal organization of that State to extremist conclusions, in that they tend to ignore completely the Lithuanian element. They even fail to present data concerning its influences, though we certainly must take them into consideration in connection with the laws and organization of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (to mention only, exempli gratia, the institute of ‘Koymintsy’).

The Lithuanian element aside, the Slav element of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania itself was not homogeneous. We have here two nationalities – the Ukrainian-Ruś and the Byelorussian. The Ukrainian-Ruś lands, with the exception of Pobuzhe and the Pinsk region, were connected only mechanically with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. They stood apart, lived their own life, and with the Union of Lublin became part of Poland. The Byelorussian lands, on the other hand, were very closely connected with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Their influence was considerable in the country’s socio-political system, in its laws and culture, while at the same time they came under the powerful influence of the socio-political and cultural processes of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, remaining part of it to the end. Thus the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is much more closely linked with that of the Byelorussian nationality than with the history of the Ukrainian-Ruś nationality, which came under its influence but had little influence in return (indirectly, insofar as the Byelorussian nationality transmitted its laws and culture which stemmed from the Kievan State; and also indirectly, by way of the political activities of the Lithuanian government, the Ukrainian-Ruś nationality adopted certain features from the Byelorussians as, for example, the elements of legal terminology in use by the Lithuanian government).

The inclusion of the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in ‘Russian history’ will not therefore take the place of the pragmatic outline of the particular histories of the Ukrainian-Ruś and Byelorussian nationalities. In the historical presentation of the social and cultural processes in the development of the Ukrainian-Ruś nationality, one might note several incidents in the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that were of particular significance [5]. The greater part of this would also be included in the history of the Byelorussian nationality; but to include the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a whole in the ‘history of Russia’ is unreasonable. If it is to be not a ‘history of Russia’, meaning a history of all that ever took place on its territory, of all the nationalities and tribes that live there (it seems that nobody presents the problem just that way though it might be done), but a history of the Rus nationalities or East Slavs [6]. (I sometimes employ the latter term to avoid confusion which results from the inaccurate use of the word ‘Russky’).

In general, the history of the organized state plays too great a role in the presentation of ‘Russian history’ or of the history of the East Slavs. Theoretically it has long been accepted that in recording the life of a nation emphasis should be transferred from the state to the history of the people and society. The political factors and those of statecraft are important, of course, but in addition there are many other factors – economic, cultural – which may be of greater or lesser importance and significance, but which in any event should not be left out.

In the case of Ruś or of the East Slav tribes, the factor of statecraft was of greatest significance and was most closely associated with the life of the people in the Great Russian nationality, (though here too, outside the boundaries of the Volodimir-Moscow State, we find such forceful phenomena, as the ‘viche’ system of Novhorod-Pskov). The Ukrainian-Ruś nationality has lived for centuries without a national state and has come under the influence of various organized states. These influences on its national life should be noted; but the political factor in the course of centuries of statelessness must inevitably play a less important role than the economic, cultural and national factors.

The same should be said about the Byelorussian nationality. In this case the Great Russian national state becomes an historical factor beginning with 1772. Its influence on Ukraine was a century earlier, but was not felt extensively. The unique and exclusive significance that the history of the Great Russian State has in the current scheme of ‘Russian’ history arises out of the substitution of the term the history of the ‘Russian people’ (in the meaning of the Ruś people, the East Slavs) for the history of the Great Russian people.

Generally speaking, what is referred to as ‘Russian history’ involves a combination of several concepts or rather a competition between several concepts:

- The history of the Russian State. (Formation and growth of the state organization and its territory).

- The history of Russia, that is, the history of the events that took place on its territory.

- The history of the ‘Ruś nationalities’. (Or East Slavs: Russians, Ukrainians and Byelorussians – ed.).

- The history of the Great Russian people (in terms of state organization and cultural life).

Each of these concepts, logically pursued, might become a justifiable subject for scientific presentation, but by combining these various concepts, none receives a complete and logical evaluation. The subject most relevant to the term ‘Russian history’ is the history of the Russian State and of the Great Russian people. With some pertinent changes it can be transformed into a logical and fully developed history of the Great Russian People. ‘Honor and renown’ to the history of this largest of Slav nationalities, but regard for its priority and its significant historical role in no way excludes the necessity for just as complete and consequential a treatment of the history of the other East Slav nationalities: the Ukrainian-Ruś and the Byelorussian.

The history of the Great Russian people can never take the place of the history of the East Slavs and of the governmental and cultural processes involved. No amount of rationalization offers anyone the right to ignore the history of the Byelorussian nationality and still less that of the Ukrainian-Ruś ; or, as is the practice now, to provide substitutes out of the sporadic episodes of the two nationalities and patch them into the history of the Great Russian people.

For that matter, I am sure that as soon as ‘Russian history’ is honestly and consequently reformed into a history of the Great Russian people, its national and cultural life, then the histories of the Ukrainian-Ruś and Byelorussian nationalities will in turn find their proper places alongside that of the Great Russians. But first of all, one must bid farewell to the fiction that ‘Russian history’, when at every step the history of Great Russia is substituted for it, is the history of ‘all-Russia’.

This point of view is still quite tenacious. In my opinion, insofar as it is not the handmaiden of politics, it is an anachronism – the old historical scheme of the Moscow historiographers, adapted to a certain extent to the demands of modern historiography. Basically it is quite irrational. The history of Great Russia (that is, its history beginning with the 12th-13th centuries) with the Ukrainian-Ruś (Kiev) beginning attached, is but a crippling, unnatural combination, and not a history of ‘all-Russia’. There can be no ‘all-Russian’ history (obscherusskaya), just as there is no ‘all-Russian’ nationality. There may be a history of all the ‘Russian nationalities’, if anyone wishes to call it so, or a history of the East Slavs. It is this term that should take the place of what is currently known as ‘Russian history’.

I have no intention of outlining in detail a plan for a new arrangement of the history of the East Slav peoples.

For fifteen years I have been at work on the history of the Ukrainian-Ruś people, drawing up a scheme for use in general study courses and in works of a special nature. It is according to this scheme that I am arranging my history of Ukraine-Ruś, and it is in this manner that I conceive the history of the ‘Rus’ nationalities. I see no difficulties in the presentation of the history of the Byelorussian nationality in a similar manner, even though it should appear less rich in detail than the history of Ukraine-Ruś. The history of the Great Russian nationality is almost ready. All that is needed is to rearrange its beginning (in place of the usual Ukraine-Kievan adjunct) and to cleanse its pages of the various episodes lifted out of the histories of Ukraine and Byelorussia. Great Russian historians and society have almost done this already.

It seems to me, that the most rational approach to the entire problem would be to present the history of each nationality separately in accordance with its genetic development, from the beginning until the present. This does not exclude the possibility of a synchronized presentation, similar to the treatment of historical material of the world as a whole, both in the interests of review as well as for pedagogical reasons.

But these are details, and they do not interest me very much. The main principles involved are to do away with the current eclectic character of ‘Russian history’, to cease patching up this history with episodes from the histories of various nationalities, and consequently reorganize the history of the East Slav nationalities, and to present the history of statecraft in its proper place, in relation to the other historical factors. I think that even the adherents of the current historical scheme of ‘Russian history’ agree that it is not without fault and that my observations are based on the errors found within it. Whether they approve of the principles which I should like see applied in its reorganization – is another matter.

Lviv, 9 (22) – IX – 1903.

Notes

[1] Written in connection with the plan for a Slavic History, prepared by the Historical Subsection of the Congress.

[2] See my remarks in the Zapysky Naukovoho Tovarystva Imeny Shevchenka (‘Annals of the Shevchenko Scientific Society’), Vol. XIII, XXXVII, and XXXIX; bibliography, reviews of the works of Miliukov, Storozhev, Zahoskin, Vladimirsky-Budanov. See also Ocherki Istoriyi Ukrainskago Naroda (‘Outline of the History of the Ukrainian People’), ready for publication.

(May I also point out that Professor Filevich, in his review of D. Miliukov’s work, published in the newspaper ‘Novoye Vremya’, made use of the comments I made relative to Miliukov’s work Ocherki po Istoriyi Russkoy Kultury (‘Outline of the History of Russian Culture’), but with their meaning distorted).

[3] This is slowly invading the sacrosanct realms of scholarship. Mr. Storozhev, the compiler of Russkaya Istoriya s drevneyshykh vremen (‘Russian History Since Ealriest Times’), for example, expresses the idea fairly clearly. The book was published by the Moscow Circle to Aid Self-Education. (Moscow, 1898). The author stressed the fact that the Dnieper Rus’ and the Northeast Rus are two different phenomena and their histories the result of two separate parts of the Russian nationality.

To avoid confusion connected with the theory ‘of the oneness of the Russian nationality’ it would be better to say ‘two nationalities’ instead of ‘two parts’ of a Russian nationality.

[4] The fine beginning made, for example, by the work of Korsakov, Merya i Rostovskoye knyazheniye (‘Merya and the Rostov Reign’), was not later developed.

[5] It was in this vein that I tried to make use of the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in Vol. IV of my Istoriya Ukrayiny-Rus’i (‘History of Ukraine-Ruś’), dealing with the period from the middle of the 14th century to 1569.

[6] One of the most recognized present systematizers – Prof. V.Budanov says that the task of the science of the History of Russian Law is the history of the ‘Russian people’, not of the Russian state. For this reason he eliminates from it the national law of the non-Russian peoples of Russia, but he considers this an integral part of the law of the Rus’ peoples which did not come into the body of the Russian state. This same view we see in other researches, although it is not consequently transferred in them the same as with V.Budanov. (See my review of his course in vol. 39 of th Zapysky (Annals) of the Shevchenko Scientific Society, bibl. p. 4).

Українська

Українська Русский

Русский

Гадаю хронологему “козацька доба” або “період козацтва” давно треба змінити на “доба вольностей”, або “період вольностей”.

1) Це звучить значно краще і точніше стосовно головних цінностей, які формували цю епоху,

2) Не лише козацтво було частиною змін суспільно-державної формації, але і селяни, духовенство і навіть окремі представниуки шляхти (напр. Стародубського полку).